Brief History

The Special Air Service began life in July 1941, during the Second World War, from an unorthodox idea and plan by Lieutenant David Stirling (of the Scots Guards) who was serving with No. 8 (Guards) Commando. His idea was for small teams of parachute-trained soldiers to operate behind enemy lines to gain intelligence, destroy enemy aircraft, and attack their supply and reinforcement routes.

Following a meeting with Major-General Neil Ritchie, the deputy Chief of Staff, he was granted an appointment with the new Commander-in-Chief Middle East, General Claude Auchinleck. Auchinleck liked the plan, and it was endorsed by the Army High Command. At that time, there was already a deception organisation in the Middle East area, which wished to create a phantom airborne brigade to act as a threat to enemy planning. This deception unit was named K Detachment Special Air Service Brigade, and thus Stirling's unit was designated L Detachment Special Air Service Brigade.

In October 1941, David Stirling had asked the men to come up with ideas for insignia designs for the new unit. Bob Tait, who had accompanied Stirling on the first raid, produced the winning entry: the flaming sword of Excalibur, the legendary weapon of King Arthur. This motif would later be misinterpreted as a winged dagger. In regard to mottoes, "Strike and Destroy" was rejected as being too blunt. "Descend to Ascend" seemed inappropriate since parachuting was no longer the primary method of transport. Finally, Stirling settled on "Who Dares Wins," which seemed to strike the right balance of valour and confidence. SAS pattern parachute wings, designed by Lieutenant Jock Lewes and depicted the wings of a scarab beetle with a parachute. The wings were to be worn on the right shoulder upon completion of parachute training. After three missions, they were worn on the left breast above medal ribbons. The wings, Stirling noted, "Were treated as medals.

Contents

How to use this book.

Acknowledgments.

Introduction.

1. Operation Titanic.

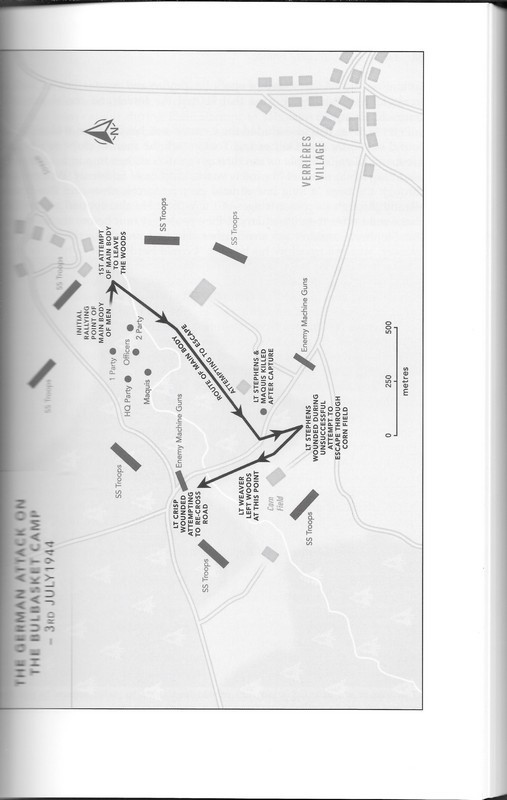

2. Operation Bullbasket.

3. Operation Houndsworth.

4. Operation Gain.

5. Operation Haggard.

6. Operation Kipling

7. Legends of the SAS.

8. The Bond that Endures.

Appendices

1. Letters sent by Airborne Corps to soldiers' families.

2. Letter sent by 1 SAS to soldiers' families.

3. Letter from Paddy Mayne to CecilRiding’s wife

4. Information sheet on health and hygiene

This offering from Pen and Sword is a battlefield reference/reading book about 1 SAS exploits and missions in occupied France is a hardback book with a stitched spine and pagination of 189.

Author Gavin Mortimer was born in London and now divides his time between the British capital and Paris. After a season or two as a semi-professional rugby player, Gavin began writing full-time in 1996 and has since contributed to a broad cross-section of publications, from Esquire to the Times and from BBC History Magazine to The Week. His first book, Shackleton, was published in 1999 and he has also written nearly a dozen children's books, on subjects as diverse as the Lakota Sioux and cricket. He has lectured on Ernest Shackleton and the SAS in World War Two to, among others, IBM, Allen & Overy, and the National Army Museum. Film Rights to his 2011 book, The History of the SAS in WW2, have been optioned to GK-TV in Hollywood, and Gavin is a frequent guest on radio stations, including BBC Radio Scotland and BBC Radio 4

Review

Since their formation in North Africa in the summer of 1941, what had started out as a small unit of six officers and sixty men known as L Detachment had undergone a radical transformation. The first mission, a parachute operation in November 1941 to coincide with the start of Operation Crusader, had ended in disaster, and of the fifty-four men who jumped into Libya to attack a string of Axis airfields, only twenty-one had evaded death or capture.

Consequently, the unit’s founder, David Stirling, had changed tactics Parachute operations were abandoned and the SAS attacked enemy targets on foot, having been transported close to their objectives in the back of lorries driven by the Long-Range Desert Group.

Operation Titanic was uncertain to go on the 19th May as planned. It must be assumed that SAS troop's commitments in the cover plan as described verbally will stand.

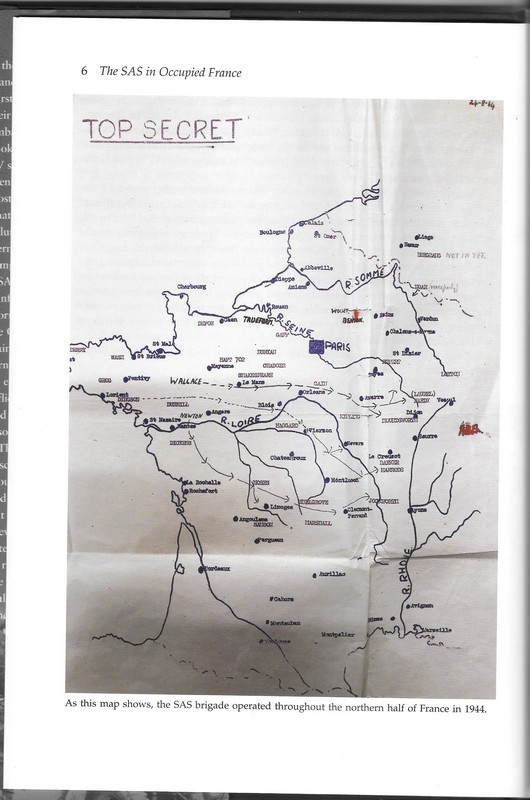

These commitments were Titanic 1: three parties of 2SAS to drop in the Yerville area, eastern Normandy, approximately 100 miles/160km east of the D-Day beaches and Titanic IV compromising of two parties of three men from 1SAS to parachute into Marigny, about 30 miles of Utah beach the western extremity of the invasion beachhead.

The six men of titanic took off from Templesford in the evening of the 5th of June and arrived over their DZ at forty minutes past midnight on the 6th of June. They were 600ft over the Normandy countryside traveling at a speed of 140 knots. In his report on the mission Flight, Lieutenant Johnson wrote all passengers jumped with alacrity and were dropped on the North-west corner of Marsh north of Le Mesnil-Vigot. The containers on the other hand were dropped slightly late due to a technical hitch in the lighting which caused them to be dropped about 10 seconds after the last man had jumped.

In fact, the six men came down 2 miles northwest of the intended DZ and the four troopers could find no trace of their officers. On landing, I found myself separated from Lt Fowles and Lt Poole; stated Anthony Merryweather, who along with his comrades, was unable to find the containers, inside which were some Bren guns, despite an extensive search. At approximately 0300 hrs the party laid their Lewis bombs (20 0f them) in an area of 500 square yards and ignited them according to Trooper Hurst. ‘By this time, it was getting light, so refuge was taken in a hedge about ½ mile north of the area.

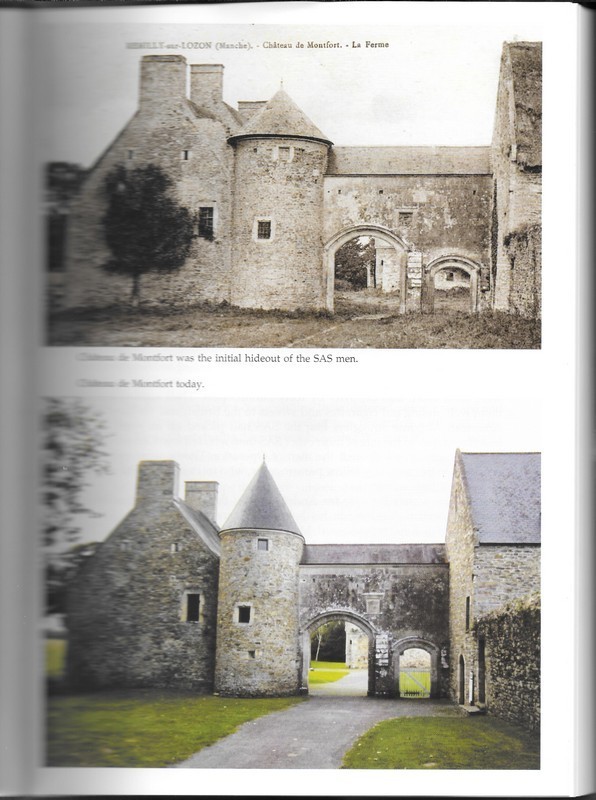

But fortune did smile on them in the guise of Andre Le Duc, a 33-year-old shopkeeper from the nearby village of Remilly-Sur-Lozon. Invalided out of the French Army in 1938 because of a serious injury, the father of seven children had been involved with the French Resistance network for some time. Despite the best efforts of the four British soldiers to blend into the local countryside, they were spotted by at least one local, who passed word to Le Duc. Hurst recalled that he arrived at their hiding at 20hrs on the evening of the 6th of June. (This is the account given to RSM Graham Rose by Hurst from his hospital bed in late August; French sources state that the SAS signaled to Le Duc during the day on the 6th of June). Le Duc supplied the quartet with food and cider which said Hurst made them ‘happy’, and during the night escorted them to the ruins of the Chateau de Montfort, about 2 miles west of the DZ and a mile north of Remilly-Sur-Luzon.

The following morning Lieutenant Poole was brought to the hideout by Le Duc, sporting a cut lip and grazed chin. He had hit his head on leaving the aircraft and lost consciousness. When he woke up he had scribbled a note to that effect and attached it to the leg of the pigeon strapped to his chest. The bird did its duty and delivered the message to SAS Headquarters.

On the 9th of June, reported Merryweather, Lieutenant Fowles arrived having landed in the next field but one to the rest of the party. He had spent the intervening period cutting telephone wires and sniping at any German who came into his sights.

Conclusion

These are just a few chapters of what is a very fascinating book completely different to what I first thought it was going to be but nonetheless an interesting read.

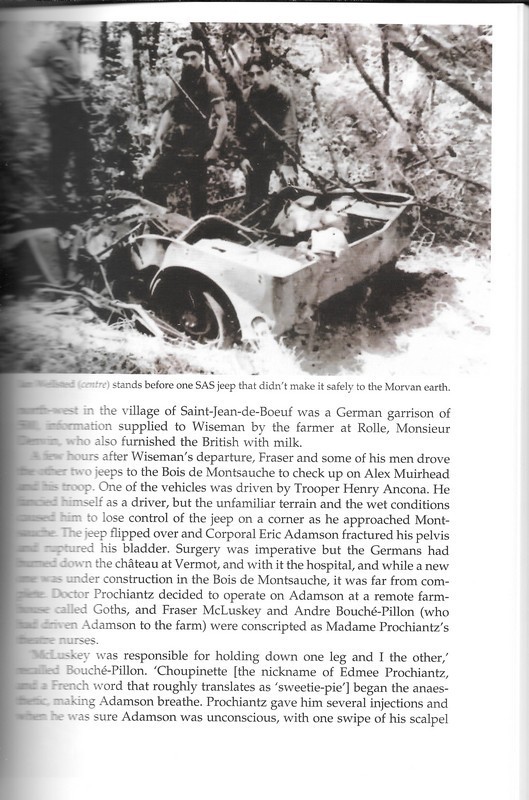

This book breaks into a part story (factual information on the SAS in occupied France) which in itself is just how I would expect the SAS doing to disrupt the enemy during wartime. The other part of this book is a battlefield guide which along with the information on the SAS but shows you places to go and visit key parts of the buildings like the Château de Montfort ruins as it was during the end of the second war and a picture of how it looks now. As a guide to the battlefield, it gives you plenty of pictures and some maps showing the routes taken by 1SAS from the night drop just before the D-Day Invasion

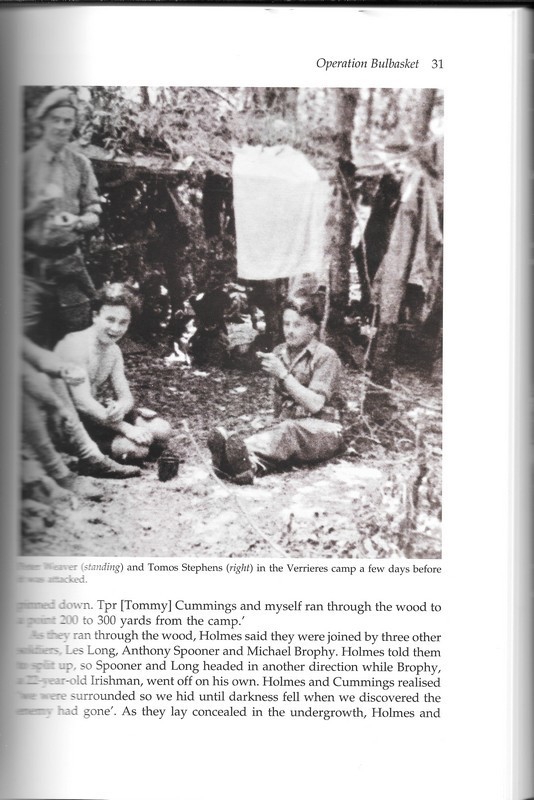

As a battle guide, it is equally as fascinating not that I have ever read one I have seen a few but this is strong in its presentation, which makes for a book easy to read and keep on reading. Now for the part where I say to you what is it going to give you, well it is certainly pictured heavy with destinations including some old photos of some of the French resistance and SAS if you are someone that has been on some of the tours of previous battlefields then I have to say yes go buy it you will not be disappointed.