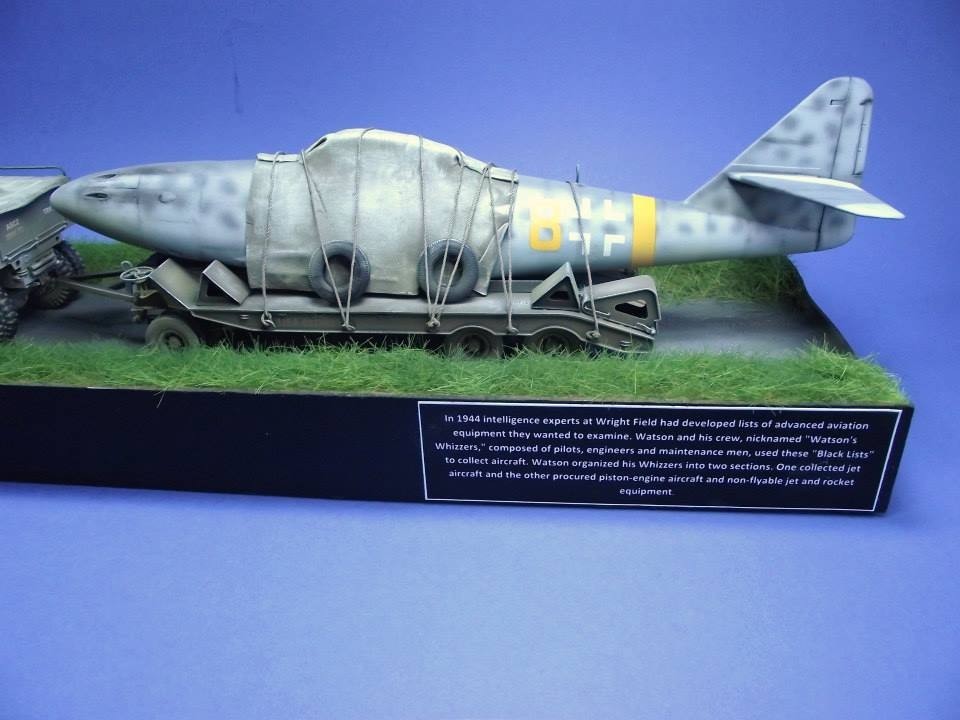

A fantastic diorama build of a Merit kit M19 U.S. Tank Transporter with Hard top and a Rogers 45-ton M9 Trailer loaded with an Me 262-1A by modelling friend Ian Miller

Operation Lusty (an acronym for Luftwaffe secret technology). The U.S. War Department opened the Air Technical Intelligence office, which, under Operation Lusty, issued “black lists” of enemy equipment it wanted to study. The lists were divided into piston-powered aircraft and jets. Watson placed the piston airplane roundup in the capable hands of Captain Fred McIntosh, but the jets generated the most excitement. On the black list: the Arado Ar-234, a hotdog-shaped twin-engine jet bomber; the tiny plywood Heinkel He-162 fighter, resembling a gecko with wings; and the Messerschmitt Me-163 rocket plane. Other Nazi weapons reflected a more desperate approach: a manned version of the V-1 buzz bomb, and a plywood rocket plane, the Bachem Ba-349 Natter, which took off vertically and carried 24 anti-aircraft rockets in its nose.

Of them all, the most important was the Me-262. The airplane that had startled Anspach was the pinnacle of the six-year-old jet age and the apex of Reich technology. A study in grace and power, it could fly at 540 mph, 100 mph faster than the P-51, yet it was only marginally larger: Its wing measured nearly 41 feet and its triangular-section fuselage stretched almost 35 feet—4 feet more wingspan and a fuselage 3 feet longer than the Mustang’s. Its boomerang-shaped wings were swept back not out of aerodynamics considerations, but to balance the plane on its nosewheel; the prototype sat on a tailwheel, and when lit the engines toasted and stripped the turf. The pod slung beneath each wing held a Junkers Jumo 004B jet engine that generated 1,980 pounds of thrust. In contrast, the experimental straight-wing Bell P-59, test-flying at California’s Muroc Army Airfield, could, even with two 2,000-pound-thrust GE engines, only hit 413 mph. Most 262s were clustered around Lechfeld, near the Messerschmitt factory runway.